Chinese novels aren’t usually given the spotlight in the Western world. Despite the country brimming with fantastic literature – both past and present – only the most avid of publishers have commissioned translations. Outside of China, you’re far more likely to encounter the nation’s cinema, as opposed to literature, but there are dozens of stunning volumes for the intrepid reader to consume.

Drawing upon the rich history of their nation, as well as the vivid plethora of emotions you would find in any successful novel, regardless of its origin, these five Chinese novelists have penned modern classics that are worth placing on your bookcase.

Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, Jung Chang (1991)

It takes a special kind of novel to achieve bestselling status, let alone beyond its native country. Jung Chang’s Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China is one such novel, with translations in nearly forty languages and an incredible global sales count pushing the 13 million mark.

It takes a special kind of novel to achieve bestselling status, let alone beyond its native country. Jung Chang’s Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China is one such novel, with translations in nearly forty languages and an incredible global sales count pushing the 13 million mark.

The story follows three generations of women in Chang’s family – her grandmother, mother and self – recounting the challenges and stories each experienced under Mao’s Communist movement. Chang captures China’s history bravely and relentlessly, not shying away from the horror and cruelty older generations suffered, so much so that the novel was (and still is) banned in mainland China. The novel is a masterpiece of courage that, in years to come, will be an even more important document of female experiences in the modern world.

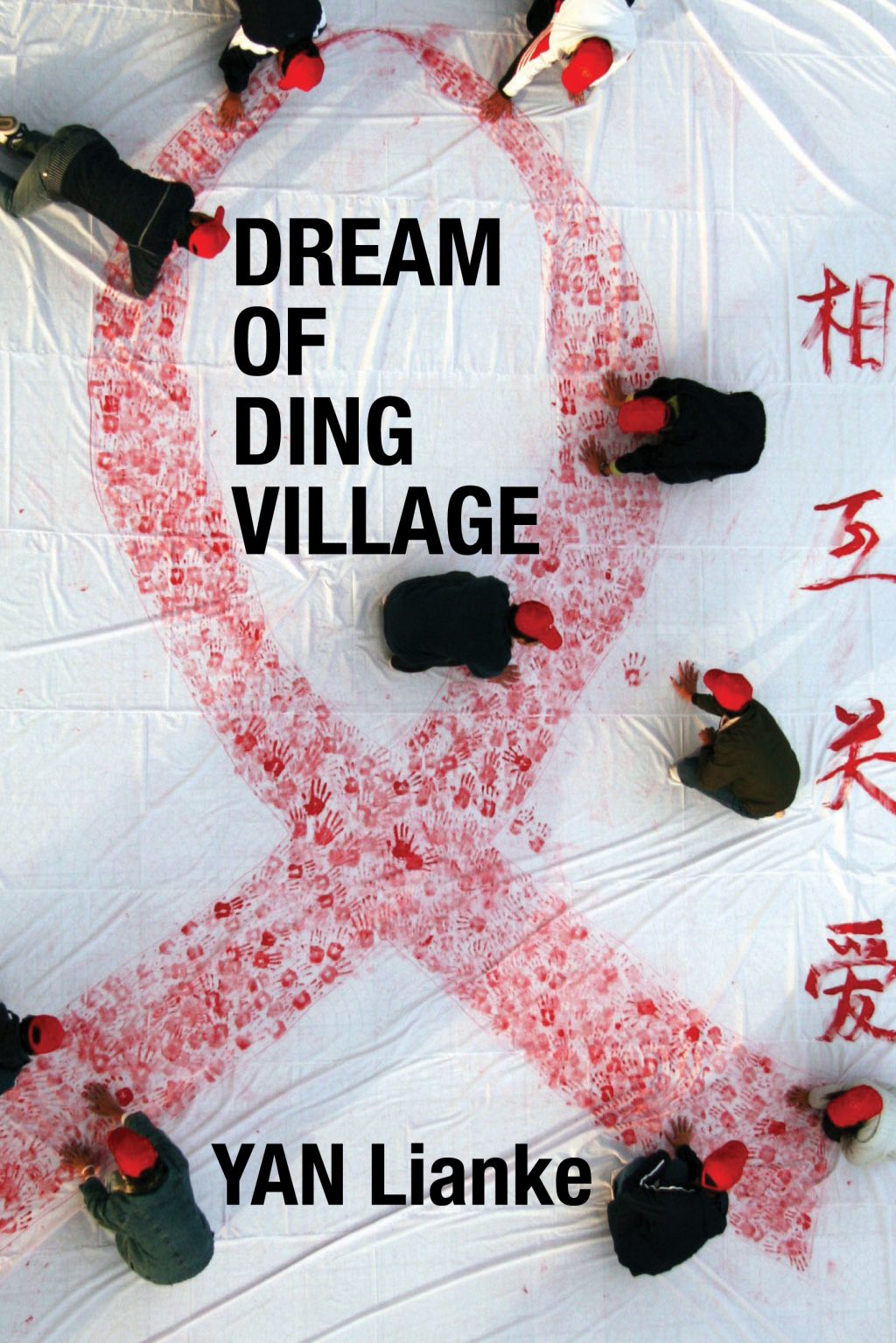

Dream of Ding Village, Yan Lianke (2006)

Another book famously banned by the Chinese government, Dream of Ding Village is a nauseating depiction based on the inhuman treatment of AIDS during the ‘blood boom’: a phenomenon from the last twenty years which saw the rapid spread of HIV among villagers due to the sale of contaminated blood. In the ‘90s, Lianke was alerted to the epidemic within his own home province of Henan via an anonymous letter, spurring him to find answers and expose the shocking effects such an illness imposes upon communities.

Another book famously banned by the Chinese government, Dream of Ding Village is a nauseating depiction based on the inhuman treatment of AIDS during the ‘blood boom’: a phenomenon from the last twenty years which saw the rapid spread of HIV among villagers due to the sale of contaminated blood. In the ‘90s, Lianke was alerted to the epidemic within his own home province of Henan via an anonymous letter, spurring him to find answers and expose the shocking effects such an illness imposes upon communities.

Although his is a fictional creation, it is a powerful look at human suffering and the corruption of governmental powers in neglecting to respond compassionately. Translated in 2011 by Cindy Carter, there is a poetry to the classic and a distressing significance that makes it still very much a prevailing part of our current times.

Wolf Totem: A Novel, Jiang Rong (2004)

The semi-autobiographical novel, Wolf Totem, is shrouded in mystery. Published under the pseudonym Jiang Rong in 2004, it was not until a few years later that the real author’s name was revealed – former Chinese political prisoner, Lu Jiamin. The novel took more than 20 years to write and has broken many records, selling millions of copies worldwide (and millions more on the black market), as well as picking up hefty bills for translation rights.

The semi-autobiographical novel, Wolf Totem, is shrouded in mystery. Published under the pseudonym Jiang Rong in 2004, it was not until a few years later that the real author’s name was revealed – former Chinese political prisoner, Lu Jiamin. The novel took more than 20 years to write and has broken many records, selling millions of copies worldwide (and millions more on the black market), as well as picking up hefty bills for translation rights.

Chronicling life in the 1970s around the remote China-Mongolia border, Rong eloquently blurs age-old fables with modern day tales to depict the dying culture of the Mongols alongside the Han Chinese farmers. The novel not only delves into the political strife of the communities, it also places a strong emphasis on the conservation of nature, using the sacred emblem of the Mongolian wolf to question the relationship between man and nature, man and animal.

Although Peter Jackson was originally set to direct a film adaptation shortly after the novel was published, it wasn’t until 2015 (coinciding with Chinese New Year) that the novel landed in cinemas, as the work of French director Jean-Jacques Annaud.

Love in a Fallen City, Eileen Chang (1944)

Often considered as one of the most influential modern writers from China, Eileen Chang’s works centre on the tensions and longing between men and women in love. Perhaps her most well-known – and adored – novel is Love in a Fallen City, which blends the two cities of Chang’s youth, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and echoes Chang’s own tragic personal life of multiple divorces.

Often considered as one of the most influential modern writers from China, Eileen Chang’s works centre on the tensions and longing between men and women in love. Perhaps her most well-known – and adored – novel is Love in a Fallen City, which blends the two cities of Chang’s youth, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and echoes Chang’s own tragic personal life of multiple divorces.

The plot follows an introverted young woman who is shunned by her family after divorcing from an unhappy marriage, until a new lover enters who has the potential to stop her path to sadness and exile. More broadly, the novel speaks of rigid family traditions, sexual politics, and psychological ambiguity, set amid a background of political strain in colonial Hong Kong. Written when Chang was still in her twenties, the novel is lyrically bound, giving a dazzling look at what it means to be a young woman.

Forty years since the novel was first published, the critically acclaimed filmmaker, Anna Hui, released a film adaptation of the same name, which was welcomed as a classic in the Hong Kong New Wave cinema movement, garnering multiple awards.

To Live, Yu Hua (1993)

Also fabulously adapted into a film (by the Fifth Generation filmmaker, Zhang Yimou, a year after the novel was published), To Live tells the transformative story of a once spoiled son of a rich landlord into an honourable and heroic peasant. Due to its dark and existential message, and its brutal social critique of Chinese life pre- and post-Cultural Revolution, it was among many other novels to be banned.

Also fabulously adapted into a film (by the Fifth Generation filmmaker, Zhang Yimou, a year after the novel was published), To Live tells the transformative story of a once spoiled son of a rich landlord into an honourable and heroic peasant. Due to its dark and existential message, and its brutal social critique of Chinese life pre- and post-Cultural Revolution, it was among many other novels to be banned.

Hua is a master of his craft though, penning a novel that is, more powerfully, a testament to human endurance. The story makes the reader look deep inside themselves, inviting you to question the very meaning of life and how the choices that we make impact upon our idea of morality.

The famous quote “Your life is given to you by your parents. If you don’t want to live, you have to ask them first” is shatteringly honest, encapsulating the irrevocable nature of birth and death.

More and more publishers are waking up to China’s literary anthology, commissioning translations of novels both old and new. If nothing else, these works provide rich insight into the nation’s heritage and turbulent history.